SPECIAL REPORT: For Nigeria, darkness has great cost: trillions of naira and over 59 years

By Taiwo-Hassan Adebayo and Jayne Augoye

Oilfields across the resource-abundant Niger Delta spew flames day and night, fired by gas associated with oil production. Daily, Nigeria flares some 700 million standard cubic feet of such gas at over 170 sites.

Nigeria’s proven reserve of natural gas stands at 202 trillion cubic feet (tcf). This includes non-associated gas — that is natural gas that exists independent of oil. The country is estimated to have about 600 trillion tcf in unproven gas reserves, making Nigeria among the top 10 gas producers in the world.

This vast gas resource – added to the other immense renewable resources such as hydro, wind and solar – means Nigeria has more than enough sources to generate the electricity its 200 million people need for economic prosperity and development.

“The electricity platform is central to the rest of the economy since it overlaps with almost all other systems,” said Emmanuel Ezekwere, who for decades held senior positions at state-owned electricity bodies like NEPA, PHCN, and NERC. The first two companies are not defunct.

In reality, Nigeria has failed to translate this energy potential to development. There is nothing comparable to what has been achieved in equally developing nations like India and Brazil. Instead, its energy sector has continued to suffer from wrong policies, financial mismanagement, low investment, neglect, infrastructure deficit, tariff exploitation, and customer disloyalty.

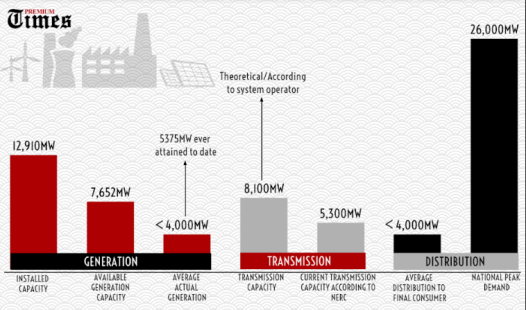

After several billions of dollars “investment”, including the Obasanjo administration’s 10 thousand megawatts target by 2007 to Jonathan’s 24,961 MW by 2019, Nigeria today, with a mostly privatised electricity industry, is only able to deliver less than 4,000 MW, about one-third of what Singapore supplies 5.6 million people.

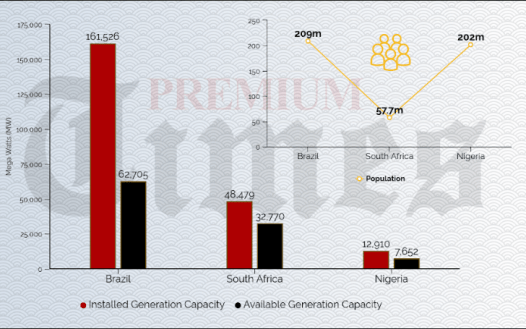

While per capita electricity consumption in Nigeria is 145 kWh, it is 8,845 kWh in the tiny Asian city-state, acclaimed for accomplishing one of history’s greatest transformation. Continental rival, South Africa, with about 57 million people, just little over a quarter of Nigeria’s population, has installed generation capacity of 48,479 MW (compared to Nigeria’s 12,910 MW) and per capita consumption of 4,198 kWh.

“After first generating electricity in 1898, we should now be talking about 40,000, 60,000, 100,000 megawatts available generation capacity,” said Sam Amadi, who headed the industry regulator, NERC, between 2010 and 2015. The first electricity generation mentioned by Mr. Amadi was 60 KW installation mainly for colonial officials in Marina, Lagos, in 1898, just 17 years after the world’s first public electricity supply in Goldaming, England.

Nigeria and Brazil have roughly similar population size but there is an alarming gap between the two Global South nations: 12,910 MW vs 161,526 MW in installed generation capacities, respectively. Further, while less than half of Nigeria’s population is connected to grid electricity, 100 per cent of Brazilians have access. The following table illustrates the differences in the capacities of Nigeria and three other countries selected from Asia, Africa, and America.

“I am not sure this is an embarrassment as that presupposes that you are surprised or have found the situation unexpected. It is our lived reality and it is basically shameful,” Mr. Amadi told PREMIUM TIMES. He decried historical neglect and infrastructural deficit, which translated to “no capacity by the time we started reforms in 2000.”

Costs of electricity deficit

To date, only 40 per cent of the country’s population has access to grid electricity, the power ministry’s permanent secretary, Louis Edozien, told PREMIUM TIMES, disclosing that “the estimate (was) extrapolated from a detailed grid power supply and mapping of served and underserved communities and clusters in five states.”

This means that as the population expands the rate of access decreases. Data obtained from the World Bank says 44 per cent of Nigeria’s then 119 million population had access to grid electricity in 1999, the year democracy returned to Nigeria. By 2019, only 40 per cent of 200 million people are connected to the grid electricity, according to official disclosure by Mr Edozien.

Several parts of Abuja, the nation’s capital, such as Gomani, Dogon Ruwa and Kutara, are among areas that not connected to electricity.

But even for the country’s populations served, blackouts are common with varying effects depending on the type of final consumers. Residents have to incur the cost of self-provided lightings such as candles, torches or gasoline for generators to watch TV or power water-pumping machine. For commercial customers, effects can include the inability to meet demands, the cost of fuel for back-up generators, and the challenge of scaling and expanding productivity.

Whether small enterprises of “hustling” young Nigerians trying to scrape together some money through fashion designing or digital marketing to stave off poverty, or even bigger businesses involved in manufacturing, the country’s electricity problem affects the productivity of these important segments of the national economy, thereby causing GDP losses and driving the soaring nature of the country’s poverty and joblessness.

“It is woeful and not helping the system,” replied Emmanuel Adebayo, the manager at a Karshi-Abuja electric pole-making company, Sunny Kunns, when asked to comment on the impact of electricity supply on his company’s productivity. “…Just about four hours a day and we have to depend on diesel, which increases the cost of production.”

As the company incurs an extra cost to get diesel to power its generator, Mr. Adebayo said this raises the price of products. “High tension pole is 37,000 Naira but it can be between 27,000 and 30,000 Naira if we use grid electricity mostly. So, as the price is higher and that affects sales, the electricity situation affects our productivity. If electricity improves, we will produce more as the price will go down and sales will equally go up, and we will employ more people.”

As the company incurs an extra cost to get diesel to power its generator, Mr. Adebayo said this raises the price of products. “High tension pole is 37,000 Naira but it can be between 27,000 and 30,000 Naira if we use grid electricity mostly. So, as the price is higher and that affects sales, the electricity situation affects our productivity. If electricity improves, we will produce more as the price will go down and sales will equally go up, and we will employ more people.”

Meanwhile, big manufacturers avoid Nigeria’s grid electricity to smoothen their operations by obtaining an independent power generation licence from NERC. Nestle (Energy Company of Nigeria), Unilever (Unipower Agbara) and PZ (PZ Power Company) are among the companies that have adopted this option since 2011.

For SMEs or other companies with lower margins, independent power generation is commercially prohibitive, and this is the reality for most of Nigeria’s businesses across scales.

“There are some of our soap making machines that our diesel generator can’t handle,” Zuwaira Shuaib, who runs Amal Botanicals Natural Baby Skin Solutions in Lagos. “When we do not have (grid) power, it can really affect us badly as we have to make the liquid soaps in small batches making it a long process for production.”

Adeleye Adeyemi of DLX Fashion in Lagos enjoys “a good supply of about 16 hours daily” at AIT Estate, Alagbado, Lagos. “This has really helped our growth,” Mr Adeyemi said. “Imagine if it is more regular than we currently have.”

A European Union-supported May 2019 report by the Capacity Building and Technical Assistance Programme, CaBTAP, says 52 percent of households and 91 per cent of SMEs use generators for at least four hours a day. Apart from the financial costs, this has implications for the environment. There are also health impacts: injurious effect of fumes and families having to spend on powering generators some money that should be freed up for healthcare or more food.

In 2014, a study by London-based CSL Stockbrokers put at $252 billion per year the cost of Nigeria’s electricity deficit to the GDP, up from $130 billion estimated by the Presidential Taskforce on Power in 2010.

However, considering the possibilities the current global economic dynamics present and Nigeria’s barely changing electricity deficit, the loss to the economy may now in the current year be in excess of $252 billion.

In 2014, the available generation capacity, according to the System Operator, was 7,139 MW, whereas the peak demand was 14,630 MW. In the current year 2019, while the peak demand has risen to 25,790 MW as the population continues to grow astronomically, the available capacity is still not more than seven thousand MW, the 2014 level. Also, for both periods 2014 and 2019, the actual generation capacities ever attained were 4,517.60 MW and 5,375 MW, respectively.

Journey to ‘terrible’ new century

Between 1968 and 1990, Nigeria completed several power generation projects, including Kainji, Jebba, and Shiroro hydropower plants, and Afam, Ughelli, Egbin, and Sapele thermal plants. By the turn of the 21st century, the combined installed generation capacity of all these infrastructures – now either privately owned or concessioned to private operators such as Mainstream Energy in the instances of Kainji and Jebba – was in excess of 5,500 MW, according to information obtained from NERC.

However, in 2000, the actual capacity was down to a measly 1,600 MW, from 1,700 MW in 1993. “Only 19 out of the 79 generation units were in operation, and of those 19, none was operating near to their design capacity,” stated Liyel Imoke, who headed the technical board of the defunct state monopoly NEPA and later power ministry. “As a result of an underdeveloped grid, the transmission infrastructure was badly constrained, while the distribution network was weak and fragile.”

Nigeria’s state of electricity at the beginning of the century followed the mismanagement at NEPA, non-provision of finances for expansion and maintenance in the pre-1999 years under dictator Ibrahim Babangida and late kleptocrat Sani Abacha, experts said.

“The expansion rate declined mainly as a result of funding problems,” said Mr. Ezekwere, then a senior NEPA official. “After Egbin was commissioned in 1986, no more investment for seventeen years in a situation where consumption was already growing by 19%. Good maintenance culture suffered as this was not given priority attention as a policy.”

Blaming NEPA, Mr. Ezekwere said, “It allowed itself to stray away from its operational standards, rules and procedures, therefore, permitting a culture of anything goes.” But Mr. Amadi, former NERC boss, was categorical about decrying the corruption at NEPA. “NEPA did not have audited accounts.”

At this period, Mr. Ezekwere said, the rate of payment for electricity was as low as 30 per cent and “there was a high level of energy theft.”

Mr. Imoke, in a submission to the House of Representatives, said the six-day nationwide blackout at the beginning of 2000 caused the urgency for reforms under former President Olusegun Obasanjo and the constitution of the NEPA technical board.

NIPP … billions for what?

The most significant yet controversial power intervention under Mr. Obasanjo was the National Integrated Power Project, which was a government-funded plan decided in 2004. The administration wanted to raise generation capacity to 10,000 MW by 2007 by building new plants (including Gbarain, Ihovbor, Odukpani, and Sapele, now under the Niger Delta Power Holding Company).

Earlier in 2002, the government had planned to build new plants at Geregu, Omotosho, Papalanto (Olorunshogo) and Alaoji. But according to Mr. Imoke, due to policy uncertainties as the government was expecting the passage of sector reform bill and the privatisation of NEPA, the four did not start as planned and were later added to the NIPP.

The NIPP also included four gas supply projects, over 100 transmission projects and 300 distribution projects. Although critics claim the Obasanjo administration’s spending on the NIPP was in excess of $12 billion, Mr. Imoke said the total projected cost was $4.5 billion and only $3 billion was “committed in the form payment to contractors, and the establishment of Letters of Credit, etc.”

But findings by this newspaper from interviews and several documents relating to the workings of the Obasanjo administration show that the NIPP was fraught with procurement irregularities and poor planning, which ultimately resulted in the failure to meet the 10 thousand MW target in 2007.

In one case, 10 contracts for transmission projects were awarded without feasibility studies, project costing by consultants and environmental impact assessments, according to a 2005 Budget Monitoring and Price Intelligence Unit, BMPIU, correspondence.

The contracts together cost N90.4 billion and were cleared by the BMPIU, the precursor to the public procurement bureau, then headed by Kunle Wahab, a former professor at OAU, Ile-Ife. “There is a need to build transmission infrastructure as quickly as possible,” Mr. Wahab said in justifying the approval despite the inadequacies he noted

In an apparent desperate effort to deliver the NIPP before the end of his administration in 2007, Mr. Obasanjo in February 2006 granted Mr. Imoke’s request to waive due process certificates for payments to contractors, the same way the former president had earlier granted anticipatory approvals for contract awards, according to a correspondence we saw.

A former minister, who served under Mr. Obasanjo and asked not to be named, said Mr. Imoke was giving the former president false impressions and “when we went touring the sites before the end of our administration in 2007, we discovered some were not even cleared yet.”

Mr. Imoke could not be reached for comment on his former colleague’s claim. Several calls to his known telephone line did not connect.

But in a 2009 submission to the House of Representatives, he said most of the engineering and p

rocurement phases of each of the projects had been completed by 2007, remaining only construction, which is the phase physically seen and “less than 20% of the contract sum.”

Between 1999 and 2007, the Obasanjo administration’s spending on the NIPP and running of PHCN was $5.25 billion, according to Mr. Imoke. But in 2010, Nigeria’s actual generation capacity was still an average of 2,500 MW, meaning less than 1000 MW was added to 1999 capacity, according to former power minister Bart Nnaji. The Obasanjo administration raised the capacity at Afam in 2002 and completed Geregu, Omotosho, and Olorunshogo (all now privatised) in 2007.

The Yar’Adua administration (2007-2010) defocused the NIPP, abandoning imported equipment at ports. “Yar’Adua’s policy knocked out the sector hugely but the misdirection and corruption started under Obasanjo,” said Mr. Amadi. It was Mr Jonathan that restarted the NIPP and completed Geregu, Alaoji, Ihovbor, and Odukpami, and Gbarain NIPPs leaving Nigeria with over 11 thousand installed capacity.

Privatisation: “Wee are stalled”

The reforms that started with the adoption of the National Electric Power Policy in 2001 and then the enactment of the sector reform law culminated in the privatisation of the power sector – the six successor GenCos and the 11 DisCos – in 2013 under Mr Jonathan, leaving only the transmission service for the government. However, though still wholly government-owned, the Transmission Company of Nigeria is now managed by Manitoba.

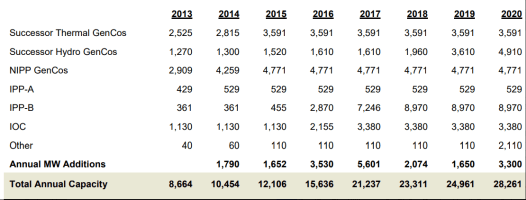

The Presidential Task Force on Power, PTFP, had in August 2013 projected 24,961 MW in installed generation capacity by 2019 and 28,264 by 2020 with expectations the industry would attract private financing for expansion. Six years after the privatisation, Nigeria is only able to achieve nearly 13 thousand MW with about 25 grid-connected GenCos, from 8,664 MW in 2013. Yet less than four thousand MW reaches the final consumers through the DisCos.

The low operational performance has happened amid falling expectations of private investment for expansion, and this, which is the consensus of operators, experts and the regulator consulted for this report, has a circularly causal relationship with the sector’s commercial performance.

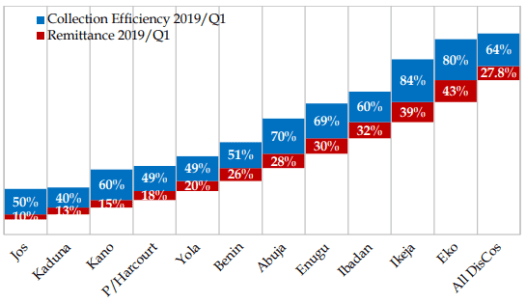

“Financial viability is still the most significant challenge threatening the sustainability of the electricity industry,” said NERC in its Q1 2019 report. “The liquidity challenge is partly due to the non-implementation of cost-reflective tariffs, high technical and commercial losses exacerbated by energy theft, and consumers’ apathy to payments under the widely prevailing practice of estimated billing.”

Bulk electricity trader, NBET, has been covering the market shortfall using public funds to shore up the revenue of the GenCos to prevent the collapse of the system. In 2018, N701 billion was released for this purpose from the CBN for 2017-2019 period.

“At the start of the privatisation, investors thought the sector was going to be self-sustaining,” said the Managing Director of Nigeria’s independent power producer, Azura, Edu Okeke, making a case for a cost-reflective tariff. “Investors cannot rely on government subsidy. It is not a reliable incentive.”

Azura currently owns the 461MW independent power plant commissioned in 2018 in Ihovbor, near Benin City. But that is just the first phase of a 1,500MW facility planned. Mr Okeke told PREMIUM TIMES that the company’s plan was to continue with the second phase immediately after the delivery of the first, which was built in two years between 2016 and 2018.

“We thought the EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) contractor would just move to the next phase without demobilising,” he said. “But because of the Nigerian environment, rather than looking at phase II (in Edo, Nigeria), Azura is now investing in another country (Senegal).”

Last Thursday, Azura confirmed to PREMIUM TIMES the acquisition of the 115 MW Tobene power plant in Senegal, investing funds Mr. Okeke said would have been deployed in Nigeria.

Clearly, the capacity projected at the beginning of the privatisation by Mr Jonathan’s taskforce is now realistically impossible amid fears about return on private investment, underscoring another dashed hope.

For Nigeria’s electricity sector to perform well, there must be technical and commercial alignment, said Sunday Oduntan, an executive director of the Association of Nigerian Electricity Distributors, ANED. “If you want DisCos to distribute 10 thousand MW, you must install generation infrastructure that produces 10 thousand MW and transmission infrastructure for 10 thousand MW, and to make the investment that brings this level of capacity, you must have confidence you will recoup your investment.”

“We are now stalled,” said Mr Amadi, commenting on the state of the industry. “We were carried away by privatisation drive in 2010. We were privatising what did not exist. We should have first concentrated on building our capacity. The other countries like Brazil first built their capacity to have sufficient product (power) before reforms towards privatisation. You can’t expect the private sector to develop the capacity within a short period.”

Fresh hope is now raised. The current administration of President Muhammadu Buhari is eyeing 25,000 megawatts of operational capacity in the electricity system through a new three-phase plan designed by tech giant Siemens AG.

The plan has three phases, ultimately targeting 25,000 MW of operational capacity long term, from 7,000 MW and 11,000 to be achieved by 2021 and 2023, respectively.

It is not clear yet what mode the financing would take and private investors are concerned about injecting capital given a business-as-usual scenario with regards to the tariff regime. But the government appears to be ready to lead the financing with a possible development assistance from Germany.

Agboola Akinola, a development activist, said his personal experience showed the country had made no progress. In September, as he sat with his twin nephews under a gasoline-powered light bulb in Oyo Town, to guide them on their school assignments, he drew the gloomy comparison.

“In the year 2000 when I was a schoolboy like these kids, this was my experience; no electricity for my assignment and I had to use a kerosene lantern,” said Mr Akinola. Today, “no change!” he added.

Comments are closed.